Coming from the wine industry, I realise the importance a barrel holds in wine making. For a decade now it has become quite sought after in the spirits and beer industry as well. So where do these barrels come from, and what’s the story behind the wood?

Greek and Roman armies quenched their thirst with wine, not water, as there was always a fear that water could be easily poisoned. So they carried with them wine in clay pots called ‘Amphorae’. The Celts, on the other hand, were craftsmen from northern Europe and used palm wood barrels instead of amphorae.

The Gauls were also highly skilled in barrel making, but they often used wood from oak trees that were widely available in Europe. The craft got passed on to the Romans, who found that oak barrels were easily transported and wine tasted better when kept in them.

Today, barrels are less important as vessels of transport; their seminal value comes from acting as holding containers for ageing liquids.

Barrel production

I’ve been living in Bordeaux (France) for the last 6 years and have visited several cooperages. One of them was Tonnellerie Nadalié, up in the Medoc. As I entered their vast premises, I noticed many stacks of oak staves (neatly cut planks of wood) arranged outside for air drying.

My host explained that they needed to weather for a minimum of 2 years before they could be turned into barrels. This process of seasoning allows the wood to dry naturally.

As we entered the cooperage, I saw a few coopers hammering on wood and metal rings to make it fit as tight as possible to avoid leaks. I realised that barrel-making was still a very traditional craft that needed more manual labour and less help from machines.

As my host led me on, I noticed a section dedicated to toasting. Each unfinished barrel was carefully placed over burners with a fire blazing inside. The intense heat caramelised the sugars in the wood. This purifies the barrels and eliminates bitter tannins.

The charring duration depends on the different level of toasts desired. Many wineries and distilleries purchase barrels and use them to distinguish their style of making wines and spirits.

Toasting barrels brings a depth of flavour and aromas, making its contents even more complex. The porosity of wood allows little pockets of air to seep through and this process is called micro-oxygenation. It allows the wood to interact with the liquids, absorbing some of it, imparting flavour compounds and tannins in the process.

Flavour formula

Tannins help a great deal in ageing spirits or wines. On the contrary, too much of it will overpower the beverage and make it bitter and astringent. Toasting eliminates tannins in the wood and adds to the flavour of the liquid.

Some barrels are toasted light, some medium, others medium-plus, and the rest heavy or char. If the winemaker wants to obtain a fuller flavour with notes of vanilla, caramel and oak, medium heat is applied.

If they desire a more toasty style, rich with complex aromas of vanilla, brioche and spice, then a stronger temperature (medium-plus) is used. If an intense mix of coffee, smoky, butter, vanilla, sweet spices profile is desired, then a heavy toast could be ideal. Lightly toasted barrels deliver more tannins and fewer aromas.

I also noticed that the coopers sprayed the barrels with water at regular intervals. The wood at this point is malleable and can be easily arched and tightened to give it its shape. Once the barrels are ready they are tested to ensure they are water-proof.

The accuracy of the barrel depends entirely on the craftsmanship, which demands up to 10 hours of manual work by experts. The average price of a single French oak barrel is somewhere around US$ 900, and could go as high as UR$ 3,500 depending on the quality.

Sourcing oak

Of the 500 species of oak trees grown around the world, 10 are found in France. However only two varieties, pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) or sessile oak (Quercus petraea), are used to make barrels. These are mainly sourced from forests in Allier, Limousin, Nevers, Tronc?ais, Vosges and Bertranges regions of France.

Wood auctions are held in September-October each year. The 100-year-old (or older) oak trees are sold to the highest bidder, and deals could run into millions of dollars! The finer the wood grains, the more value it has because of its ability to transfer complex aromas into the ageing wine or spirit. The larger the grain, the more tannins are imparted.

The logs are hand-split to preserve the wood grains. This is crucial because the barrels must be kept water-proof. This is a labour-intensive process and only two barrels can be made from each tree. There is always more demand than supply of barrels.

American oak is gaining popularity over the years for making barrels. The variety Quercus Alba is grown in the forests of Virginia, Missouri, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Oregon and California. Unlike French oak, the cost could range from US$ 500 to US$ 1,000 a barrel.

American oak logs are denser and can be easily sawed and are cost-effective. Californian wines aged in American oak present a stark difference from the ones aged in French oak and the wines tend to be bolder and fruiter, with tons of vanilla, coconut, sweet spice flavours and aromas.

There is also an increasing demand for Eastern European oak from Hungary, Slovenia and Romania. The species of oak is the same as in France, but the barrels are more affordable alternatives. Many wineries and distilleries are experimenting with them.

Re-using barrels

Barrels are mostly used three to four times, after which they do not interact much with the liquid placed in them – unless they are reconditioned. This can be achieved in two ways.

One is by deconstructing the barrel completely and then shaving off the interior of the staves to get rid of tartrates. They then need to be cleaned, re-toasted and reconstructed in the same manner as new barrels.

The second method is done by blasting the barrel with dry ice. This removes all the tartrates. The toast is intact, so there is no need to shave, deconstruct and re-toast the barrels. Reconditioning a barrel could cost up to US$ 300. This is not only cost-effective, but it also prolongs the life of a barrel.

The used-barrel marketplace has gained popularity across the globe. Whiskey casks are often in demand for ageing beer to impart a complex tapestry of flavours: tobacco, chocolate, cherry, oak and vanilla.

Sweet and red wine barrels are regularly sought for finishing whiskey. This final interaction with the barrels adds sweetness and fruitiness to the whiskey, which already has smoky tobacco flavours.

Sherry butts too are in demand for ageing whiskey. Olorosso and Amontillado butts, add colour and nutty flavours. Craft gin producers play with a variety of barrels ranging from white wine, red wine, port wine to whiskey casks.

Size matters

But why are barrels also called casks, butts, hogshead, etc.? The sizes of barrels across the world vary greatly. The smaller the barrel, the higher the impact of oak attained, and vice versa. In France, Bordeaux winemakers use the standard 225-litre barrels, while the Burgundians use 228-litre barrels.

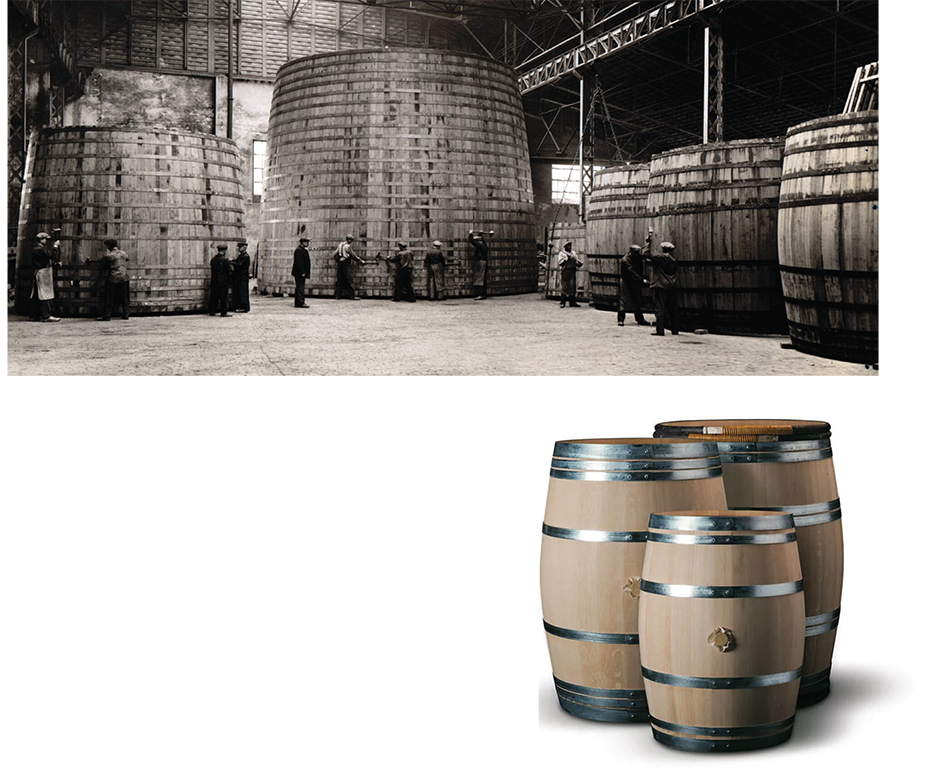

These are referred to as Bordeaux barrique and Bourgogne barrique. Less common are the 500- and 600-litre (demi-muids) barriques. The largest ones are called foudres, which are usually in the size of a big vat.

In the world of whiskey, barrels are often referred to as casks. American standard barrels are made to hold 200 litres and are made of white American oak. These are commonly used to mature Bourbon whiskey.

Hogsheads are made from staves of a Bourbon cask with new oak ends and hold a capacity up to 250 litres. Butts are used in the making of sherry. It can easily fill 500 liters of liquid in it.

Port barrels are called pipes and Madeira barrels are called drums. Pipes have a capacity of 550 litres and drums hold about 650 litres. These are fabricated in Portugal for ageing port wine, after which they find use in finishing Scotch whiskies.

The barrel industry has grown in popularity over the past decade as more and more distilleries and breweries turn to them to produce award-winning craft beverages. Understanding what flavour profiles can be achieved through interaction with barrels and sourcing from different countries can be overwhelming.

So, if you are looking for new barrels, second-hand or refurbished barrels – or simply seeking advice on which barrels to use – you can write to me at namratha@wine-equation.com.

Bordeaux winemakers use the standard 225-litre barrels, referred to as barrique (L). The largest ones are called foudres (R), which are usually in the size of a big vat.