A handful of talented distillers and blenders, even hands-on brand owners, are turning the global spotlight on the Indian alcobev industry, and how!

Amrut Distilleries’ Ashok Chokkalingam switched from the sales side to Head Distiller last year. His favourite is the Amrut Spectrum single malt (R), aged in different oak casks.

Over the last 5-10 years, one noticeable trend in the Indian alcoholic beverage industry is the emergence of a set of spirits brands at the premium end. These have caught the fancy of consumers, not just in India but also overseas. Many of them are well on the way, if not already there, to be commercial successes.

This story started with Amrut Distilleries in the single malt whiskey segment, followed by Paul John Distilleries and then Radico Khaitan. What is doubly refreshing in a category like single malt whiskey is that these brands have also built thousands of loyal followers and fan clubs around the globe, who keep a close eye on what’s their next innovation.

Demand has also been so explosive in the overseas markets that, to cite just one case, a company like Amrut indicates a sales loss of over Rs. 20 crore due to unavailability of stocks.

Their efforts have also received validation from leading influencers in the global whiskey industry. Paul John’s Mithuna recently ranked as the 3rd best whiskey in the world in Jim Murray’s 2021 Whisky Bible. A similar recognition was earned 11 years ago by Amrut’s Fusion single malt.

Young enterprises

Taking inspiration from these instances of success, first-generation entrepreneurs have emerged to set up spirits companies and brands. Riding on a global wave, their first choice of product was gin.

Nao Spirits (Greater Than and Hapusa) and Third Eye Distilling (Stranger & Sons) are the early trendsetters. The success they’ve enjoyed in helping define and develop an Indian dry gin category and starting exports have led to scores more entrepreneurs entering the gin category.

The success enjoyed in gin has led to further investment in these companies, which provide welcome capital for them to now build product pipelines in categories such as rum and whiskey, the latter requiring deeper pockets and more patience due to long maturation cycles.

Linked to this is the effort by some other entrepreneurs to markedly raise the game when it comes to native spirits derived from Mahua and cashew fruit (Feni). In the case of Mahua, the spirit has emerged from its rural base to being commercially produced for the first time in India.

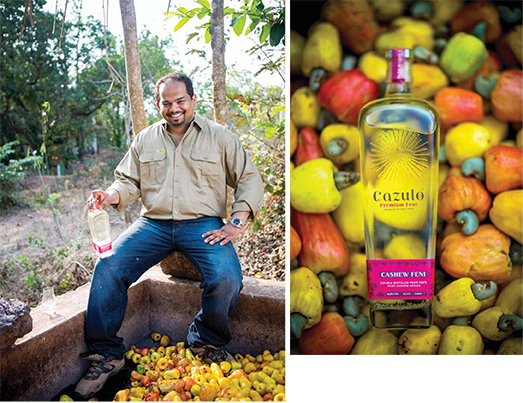

In the case of Feni, entrepreneurs like Hansel Vaz of Cazulo and Regan Henriques of Rhea Distilleries first started with raising the profile of Feni and are now turning their attention to innovation such as barrel ageing.

They are resurrecting old practices and craft, and trying to preserve the last of a dying breed of distillers.

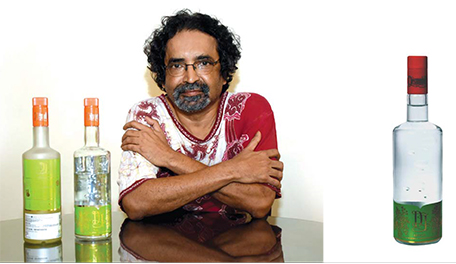

Desmond Nazareth of Agave India has done pioneering work in not only exporting agave-based spirits, but also elevating Mahua (R) to international standards of distilling and distribution.

Experimental minds

All of what I’m describing would not have happened without the people’s drive and energy at the head of these firms; but what is equally important is the blenders and distillers who have turned this vision into products that have found commercial success and critical acclaim.

In Indian single malts, the technical teams are led – more than ably – by Michael D’Souza at Paul John, Ashok Chokkalingam at Amrut, and Anup Barik at Radico Khaitan. They’ve taken different paths to where they are now, but have all been driven by the passion for creation and constant experimentation.

Anup is possibly the most fortunate in that he comes from a family of blenders, who have also served the Indian alcobev industry for three generations – Anup’s brother, Arun, is the technical head at Allied Blenders and Distillers.

Both Anup and Michael joined the alcohol industry after graduation. While Anup was following a family legacy, Michael had an early fascination with the making of alcohol. Both have risen steadily in their respective organisations over roughly a similar period of 27 years.

On the other hand, Ashok started on the business side, having headed Amrut’s single malt business since 2004. After the previous technical director, Surinder Kumar’s retirement, Ashok took on additional responsibility as Head Distiller since June of last year. He is on the verge of finishing a Diploma in Distilling from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling, London.

For Charnelle Martins of Third Eye Distillery, which manufactures and exports Stranger & Sons gin (R), science education is a must to empower the next generation of distillers.

Scotch fixation

What is admirable in all their cases is that none of them, at the start of their careers, had either any formal qualifications in distilling or blending – none still exist in India, and the only option is to go abroad.

Nor did they have access to the research and development infrastructure that any multi-national could take for granted in Scotland or Kentucky. However, they used their intimate knowledge of the Indian market, combined with quick decision making at the top, to unleash a relentless wave of innovation, especially in the case of the early movers like Amrut and Paul John.

They were both also helped due to the men’s vision at the top of their companies – N.R. Jagdale for Amrut, and Paul John for his eponymous whisky – who were determined to put Indian whiskies on the world map.

What puts these achievements in perspective is that the Indian consumer has a keen preference for Scotch whisky, and as a result, also has that taste ingrained in his/her mind.

Paul John Distilleries’ Master Distiller, Michael D’Souza (L) is seen at work with Brand Ambassador Yash Bhamre. (R) The new Mithuna single malt whiskey expression, which was rated by Jim Murray as the third-best in his 2020 Whisky Bible.

‘Visualising’ aromas

Considering that these Indian single malts cater to Indian and overseas audiences, Ashok and Michael have had to mix up their product portfolio accordingly, with the more dramatic innovations for the export markets and sticking to the traditional Scotch whisky palate for the Indian market.

Anup of Radico Khaitan says, however, that there has been a huge shift of consumer behaviour with the increasingly knowledgeable consumer now open to experimentation.

Anup also believes in “visualising the product”, where he talks about “the importance of visualising the aromas that you want from it”. This, he says, is a complicated process compared to visualising what you see, hear, or even taste. “But once you imagine this, everything falls into place,” he says.

Ashok of Amrut corroborates this: “Indian consumers speak the whiskey language now. We have come to a stage where it is no longer necessary to distinguish the Indian palate and nose at the top end of the market. The status quo in terms of the palate is more in the low and mid-segment of the market.”

Michael differs in saying that the Indian palate is still one that is in evolution, with the preference for sweet and elegant whiskies. This has, in turn, led to a marked taste for Nirvana, Paul John’s entry-level single malt.

Most importantly, it is the complexity of the end product that they are producing: single malt. Michael says, “From selecting the ingredients to manufacturing, selecting casks to maturing of whiskies, everything has to be designed as per our environmental conditions.”

Due to extreme temperatures in India (similar to Kentucky), maturation takes place at a much faster rate than an equivalent spirit in Scotland. This requires expert judgment on our distillers’ part, honed over the years when it comes especially to maturation.

India also does not have a robust manufacturing ecosystem when it comes to pot stills. Our distillers have also had to work with local manufacturers, to get this critical piece of equipment made to their design specifications.

Nao Spirits’ Anand Virmani says Indian craft gins, such as his Greater Than (R), have great potential in offering botanicals and flavours seldom found abroad.

Owner-distillers

If Indian single malts have put the spotlight on our industry’s technical stalwarts, what is hugely encouraging is the emergence of a young generation of distillers. They are now working on extending the product pipeline of their companies and actively engaged in research and development, while at the same time exploring the potential of Indian ingredients in their recipes.

The first product that they have focused on is gin, with Indian craft gin becoming quite the rage over the last 3 years. The seeds (or shall we say juniper!) that they have sown have led to those initial three-odd gin brands now multiplying into nearly double figures.

In many entrepreneur-driven start-ups, the entrepreneur has also doubled up as blender/distiller, creating a closer connection between the vision and execution. This has been a truly remarkable accomplishment for Nao Spirits and Third Eye Distilling.

Anand Virmani, a co-founder at Nao Spirits, led the charge when it came to the production side. The company was fortunate enough, however, to have been assisted at the start by Dr. Anne Brock from the UK, who helped them in early product development and setting up distillery operations.

Anand has a history of working with William Grant & Sons and Remy Cointreau, in between picking up an M.Sc. in Wine Business in Burgundy (France).

For Stranger & Sons, the product development was led by the founders, Sakshi, Rahul and Vidur, who undertook a distilling course in the Netherlands conducted by their suppliers of stills.

Charnelle Martins has since taken over as the head of distillery operations. Previously working with Diageo-India, Charnelle is possibly one of the most technically qualified distillers working in India. She followed up a Masters in Food and Alcohol Bio-technology from Scotland with an internship at the Scotch Whisky Research Institute, and then finally a Diploma in Distilling from IBD, London.

Hansel Vaz has rejuvenated Feni-making traditions and practices to put back the fire in his Cazulo brand (R).

Masala box

How do gins from India differentiate themselves in the export market? Charnelle says the answer lies in “the masala boxes in our kitchens”. The key to gins made anywhere in the world, especially when it comes to product innovation, is new botanicals that can be introduced, and those flavours are where India has a lot of potential.

“Gin is a versatile and approachable spirit and gives a distiller enough room to experiment freely. As an Indian-spirited gin, Stranger & Sons boasts a robust and distinctive blend of spices with a truly Indian provenance.” Charnelle says.

Anand corroborates by saying that there is indeed an opportunity in creating a niche for Indian gins around the world. He adds that although they might lack the resources a multi-national can summon, craft gin distillers can bring “a level of energy and excitement to the R&D process that might be difficult to replicate by a bigger firm”.

The “gin wave” in India has opened the door for innovation. ‘Perry Road Peru’ is the first distilled cocktail launched recently by Stranger & Sons in collaboration with The Bombay Canteen. The upcoming ‘Juniper Bomb’ from Nao Spirits is another example.

Native spirits

While gin is very much the flavour of the year, let us not forget those techpreneurs who are reviving/reinvigorating Indian native spirits such as Mahua and Feni. These are craft spirits companies with a difference, in that they are focused on spirits from our heritage.

The first case in point is the Desmondji Mahua and Mahua liqueur, made by Goa-based Desmond Nazareth in his distillery in Andhra Pradesh. Mahua is probably the world’s only spirit that is fermented and distilled from naturally sweet flowers.

In India it has always primarily been made by tribal populations across several states in central India, prominently Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. At that small scale, where a few litres are made in their backyard, the flowers are collected locally, the complexity of distillation is limited, and there is probably the need to pay close attention to hygiene.

As the first entrepreneur in India to commercially make Mahua, Desmond had no established practices to fall back on and developed processes and procedures from scratch. That included the iterations required to get the blend correct (his current Mahua is a blend of Mahua flowers and cane sugar) and the subsequent fermentation and distillation processes.

Also critical was establishing standard operating procedures to ensure proper hygiene was maintained in collecting, drying, and storing the Mahua flowers. This plays a critical role in ensuring that the flavour comes out.

Desmond is now lobbying with different state governments for setting up of a national Mahua research institute. Once done, he would be quite happy to share the fruits of his labours with them so that other entrepreneurs can benefit.

Before Mahua, we know Des for his pioneering efforts in making the first agave spirits from India from raw material growing wild in the Deccan plateau.

Radico Khaitan’s Anup Barik followed in his father’s footsteps. He is most proud of the Rampur single malt (R) expressions.

In continuity

If we’re fortunate enough to have someone like Desmond to champion the cause of Mahua, we also have Hansel Vaz doing the same for Feni. For a while now, Feni has languished, with younger Goans preferring whiskey.

Hansel is rejuvenating and preserving the age-old practices and traditions that every Goan cazcar is familiar with. Cazulo (Konkani for Firefly) was born in 2012, when Hansel traded a career as a geologist in the South Pacific to return home and resurrect his family’s business.

He has a working cashew Feni still on the Cazulo Fazenda (farmhouse), where he has focused on improving the distillation process, hygiene and capturing the best distillate. These practices also spread to the 3,000-odd small stills that dot Goa and supply to commercial bottlers like him.

As a sceptic with unhappy memories, the difference was clear to me the first time I tasted Cazulo in 2015. It made me appreciate the fine balance that Hansel has taken in treading a fine line between making the spirit more accessible to other audiences and ensuring that it will also be acceptable to locals.

As Indian alcobev companies continue to grow what is grimly apparent is the acute shortage of trained human resources on the ground. The absence of any local institutions that offer specialised qualifications is a big gap. The only one offering some similar form of qualifications is the Pune-based Vasantdada Sugar Institute (VSI).

Ashok of Amrut thinks that as social taboos towards working in the alcohol industry diminish, it should be the market leaders’ responsibility towards some form of capability building in this area.

Internships should also supplement this in alcobev companies, feels Michael.

For Charnelle, what is critical is encouraging more people to opt for studies in science, technology, mathematics and engineering, so as “to educate and empower the next generation of distillers”.